Night of the Non-Humans 2/3 | Rat Laughter | Keynote by Kathy High | IMPAKT Festival 2019 Keynote: Rat Laughter Speaker: Kathy High

Ways In?: Processing Messages Received / PUBLIC Journal

Ways In?: Processing Messages Received, PUBLIC Journal: The Welter of Being: Interspecies Communication and the Expanded Mind, eds. Meredith Tromble and Patricia Olynyk.

Peer reviewed article, publication date August 2019.

Dear Bees and Microbes / Institutional Critique to Hospitality: Bio Art Practice Now

High, Kathy. “Dear Bees and Microbes,” Institutional critique to Hospitality: Βioart Practices. A Critical Anthology, edited by Assimina Kaniari, GRIGORI Publications, Ippokratous 43, Athens, Greece.

>>DOWNLOAD PDF

Gut Love Talk / Bio Blanket Performance

Kathy High and Guy Schaffer for the exhibition of Gut Love: You Are My Future at the Esther Klein Gallery, Science Center, Philadelphia, PA.

Gut Love: a Conversation about Poop / Sadie Starnes — The Brooklyn Rail

High, Kathy with Sadie Starnes, ”Gut Love: a Conversation about Poop,” The Brooklyn Rail: Cultural Perspectives on Art, Politics and Culture, December, 2017.

Perhaps the weird will save us from self-destruction. But we are probably doomed for self-destruction no matter what. That which is weird can provide us with alternative approaches, ways of seeing new combinations, novel relationships, and alliances. This is what will save us if anything can—maybe not from self-destruction—but from doing harm to each other, giving us new strengths and options.

—Kathy High

Kathy High is an interdisciplinary artist and Professor of Video and New Media in the Department of Arts at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. Her art practice, which is a curious mélange of video, performance, photography, speculative fiction and collaborative experimentation, integrates biotechnology and science. Concerned with technology’s influence on our definitions of gender, the self, and animal sentience, she is known for documentaries such as Death Down Under (2012-2013), which examined the ecology of death, and Animal Attraction (2000) on telepathic communication with animals. High has experimented with transgenics in a number of multimedia, interspecies projects such as Embracing Animal (2004-2006), and she has staged competitions between human white blood cells through her ongoing Blood Wars tournaments. Her recent solo exhibition, Gut Love, held at the University City Science Center’s Esther Klein Gallery in Philadelphia, investigates gut microbiota, the human immune system, and procedures such as Fecal Matter Transplant. Gut Love raises philosophical and ecological questions around post-individualism, contemporary medicine, and abjection through an array of surprising vehicles—from human waste to David Bowie to an iPhone app. A recent artist-in-residence for Coalesce: Center for Biological Arts and at the DePaolo Lab (University of Washington, Seattle), High approaches these topics with the curiosity of an artist, the objectivity of a scientist, and the sincerity of a patient with Crohn’s disease.

Esther Klein, Philadelphia

GUT LOVE: YOU ARE MY FUTURE

October 12 – November 25, 2017

Rebecca Starnes (Rail): Gut Love investigates the human microbiome through a variety of media and approaches—from the scientific and cultural to fictional and even personal. Where did this dynamic, wildly interdisciplinary project begin?

Kathy High: I am currently researching and producing art works about gut microbiota and the immune system. I have come to this work as an artist who has engaged art and biology for the past fifteen years. Questions I have asked include: How does the medical industry look at disease and immunology? What can we—as patients and civilians—contribute to this knowledge base?

I work in this interdisciplinary area of art and science, sometimes called “bioart,” because I am curious about philosophical questions concerning carbon life—and I want to approach these questions in a hands-on manner, working directly with biological systems. Bioart—narrowly defined—limits itself to that which directly involves the manipulation of biological materials. A broader, deeper interpretation embraces the questions that bioart can raise about the role of science in society and actively integrates social reflection and a critical awareness of artistic and scientific practices as part of its raison d’être.

Beyond these questions I am amazed how much media attention the human microbiome has received of late—and yet how little people really know about it. I started on the Gut Love project out of curiosity – what exactly is a Fecal Matter Transplant (FMT)? What is it used for? How can we rethink our relationship with poop? Why are we ashamed of our bodily functions? Where did this shame come from culturally, historically? These questions and others prompted me to pursue this work and to talk with scientists, work with collaborators and tease out as much as I could. I am very much still in this process. I use my own body as a starting point to all of this work.

Rail: I enjoyed seeing your show in Philadelphia, which was installed not so far from the Duchamp collection and his storied Fountain. There have been countless satirical takes on the subject of human waste in art—from Piero Manzoni’s Artist’s Shit (1961) to Terence Koh’s more recent Gold Plated Poop (2007). Your “ready-mades,” however, like the Bank of Abject Objects—a beautifully arranged installation of feces preserved in honey—take us beyond a punch line. In fact, irony is not their point, right? I was startled by how fascinating it was to closely observe a matter so ubiquitous and natural. Why is it important for humans to move away from the abjection of feces?

High: I love being listed in this excretion art history! The potential of feces for therapeutic application is now becoming recognized, and our understanding of it is changing. Feces is now potential, rather than mere waste. It can be used to treat various diseases such as Clostridium difficile (C. diff), and inflammatory bowel diseases, but there is research suggesting FMTs might also treat inflammatory disorders such as lupus, heart disease, diabetes, and even autism, and the list goes on. Currently FMTs are only legally allowed in this country to treat patients suffering from C. diff, but other trials are underway.

Gut Love, Installation view. Photo: Jaime Alvarez

In other arenas, we see value in our waste, creating urban cities’ composting programs using food waste as nutrition for soil. These kinds of transitions, processes, and becomings are all part of understanding life and death. It is a beautiful thing.

But we need to have fecal materials not only available to scientists and medical practitioners as commodities and drugs, but also made accessible to people in an open source kind of way. This is where art comes in and why I created this project of a DIY Bank of Abject Objects with (ceramic) poop preserved in honey for your future. This work is a model for at-home fecal storage. People dream of being immortal. Perhaps preserving a bit of stool when you are healthy will be a way to reset your system should you fall ill in the future. The glass containers were produced by Bill Jones and the ceramic poop by Jillian Hirsch – in the exhibition the credit reads as “Poop – Jillian Hirsch” purposely to allow for the slippage of people believing this is actual feces. The pieces are illusions of the real.

Rail: There is a parallel drawn in your presentation and the video documentary Fecal Matters between a “post-human” perspective and the complex community that is our microbiome. How deeply has Donna Haraway’s feminist cyborg or “compost-ist” theory influenced the work?i

High: Haraway’s writings have been hugely influential in my work for years. Her reference to Oncomouse©^2 as her sibling in Modest-Witness@Second Millennium influenced my project Embracing Animal. And for this work, Fecal Matters, Haraway’s writing about our relationship to cyborgs alongside non-humans and companion species are all compelling rethinkings of “otherness” without falling back on binary oppositions. Such texts as “Cyborg Manifesto” (1984), When Species Meet (2008), The Companion Species Manifesto (2003), and others. As Haraway has discussed, “post-human” is a loaded term and one she has moved away from, considering it “too restrictive.”i The term often points to techno-futures and often does not resituate us in relation to other companion species with whom we are bound. Haraway herself has written: “We have never been human.” And if we rethink this statement slightly and consider Dr. Emma Allen-Vercoe’s comment that “we are not just human,” we begin to understand that we have a responsibility to the other microbes living amongst us—as companion species. We co-habit, we co-mingle, we co-create. If we stay with this concept, things can get stinky, wet, and very messy. For me, this understanding raises lots of ethical considerations about how I do or do not take care of myself. To consider that we are only about 50% human cells and the rest bacteria, fungi, and viruses—this shifts our sense of self-identity. Now, we understand that we are literally not “I” but “we”—creating a sense of community which hopefully can even influence social, environmental, and ecological encounters. I am still only just beginning to come to terms with these concepts.

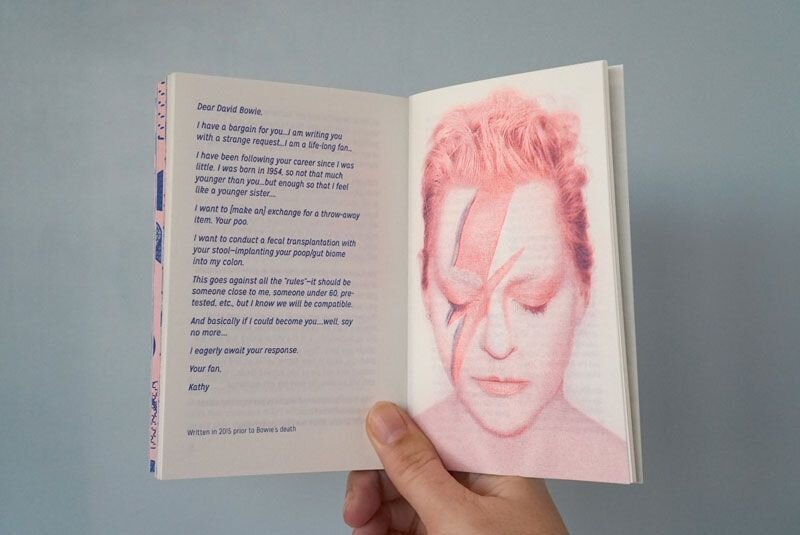

Rail: As a fluid, shape-shifting artist, was David Bowie meant to be an example of this “post-human,” symbiotic microbiome? Could you talk about how and why you shot the “Kathy as Bowie” series in 2015 as well as how you came around to requesting not his autograph, but his poop?

High: A dear friend of mine, performance artist Kira O’Reilly, once asked me if I could have a FMT, whose stool I would ideally use. And without hesitating I responded that I wanted David Bowie’s poop. I was kind of surprised by my own answer, but as I thought about it afterwards, I realized that was the right answer. Bowie had been influential in my own identity creation. And I felt if I could have a little bit of his poop, I would inherit that Bowie specialness through his bacteria and gut microbiome. And, as you noted, Bowie definitely was someone who constantly changed and recreated himself, much like a well-tuned symbiotic system taking note of his cultural surroundings, always pushing boundaries and expanding ways of living.

I sent the photos off, offering them the photos in exchange for a poop sample, but I never heard from Bowie. I didn’t know he was ill. Sadly, it was the last year of his life, and he had many other projects he was working on at the time.

Rail: Speaking of shape-shifting, I’m curious about the creation of Challis Underdue for MIT’s The History of Shit project. In the exhibition, you present the fictional history of a 19th century pioneering female proctologist. The history of shit suddenly shifts to the history of women in science, illustrated in a persuasive display of photographs, scholarship and beautifully rendered glass colons. Guy Schaffer’s extensive research on “The Forgotten Scatomancer” is incredibly detailed, to the point of quoting from her diary. What inspired the creation of Challis Underdue? Was the aim closer to another Bowie parallel (in a creation of alter-egos), an exercise of feminist science fiction, or both? How did the Science Center feel about presenting such convincing documentation of a fictional figure?

High: Collaborator, Science Technology Studies scholar Guy Schaffer and I have been talking about publishing a “history of shit” perhaps picking up somewhat from where Dominique Laporte left off with his book of the same title.ii When I was thinking about the Gut Love exhibition, I mentioned to Guy that we might start the process of creating our book by making a series of exhibitions to inspire us. Then we were lucky enough to receive a Wood Institute Travel Grant from the Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia to conduct research in their amazing Historical Medical Library and the Mütter’s object archives.

Once we had completed our Mütter Museum research, we were confused about the direction we should take. We had researched so much great material form the 18th and 19th centuries, but how to present it? Then I came up with the idea of writing a fictional historical character to embody the research and create a story. Another collaborator, artist Oliver Kellhammer,iii prompted me by asking about this character’s gender — and while at first I thought the character should be male as they were dominant to that medical history, suddenly (thanks to Oliver!) it became clear that having a female character was an opportunity to rewrite that history! Also I was excited about inserting myself as a 19th century alter-ego — creating a character so intrigued by poop that she defied the research trends of her day (germ theory) and stuck to her belief in the miracle of feces, an idea that was out of favor during her later years. So the story is, as you noted, a feminist rewriting of history. Guy, as an educator of the history of medicine in the Science Technology Studies department of RPI, was very interested in historical fiction as it is a means to embody and bring the past to life. (He liked this exercise so much, that he has now given his students a historical fiction assignment.)

I had not even thought about the parallels of the Challis Underdue alter-ego I was playing to the David Bowie character until later. All of these alter-egos—and literal embodiments—do help me understand both myself and the characters better. Challis’ wig changed my look so dramatically that I felt of another era and age. The name Challis came from my maternal grandmother’s first name Challis (ironically she was a Christian Scientist practitioner), and Underdue was a name I saw written on a hotel billboard for a family reunion “We welcome the Underdues!”—and the name seemed so funny and perfect that I co-opted it.

Regarding the perception of the fiction/fact aspect of the work: Guy and I agreed that we wanted the exhibition and story to appear plausible. This suspension of disbelief and possibility for such a person to exist — such as Challis Underdue — was important to us. In an art context, I think this is okay. Besides, this is a queer history, and I mean queer in the fullest sense of the word. We decided to bring it all front and center and excite the public imaginary.

Rail: In a performance during the exhibition, petri dishes full of bacteria are smeared on your stomach—a treatment meant to relieve your Crohn’s disease. Could you explain dermal transplant, and have you felt any improvement in your condition since?

High: This performance was the first time I have attempted to work with the dermal transfer, and so I have not had a chance to really test the results. I did feel kind of high after the performance so there was a buzz effect produced. But I didn’t really do it long enough to make much effect. Having the warm agar and bacteria on my belly was delicious though, and smelled great too. Someone said it smelled like baking.

Because of the questions about whether probiotics are really effective, and questions about the risks of FMTs, I wondered if a dermal transfer of specific bacteria (that I am actually lacking) would allow my system to absorb those specific bacteria to replenish the gut microbiome. It is just my own theory. The dermal transfer(s) probably will not relieve my Crohn’s disease, but it might aid my gut bacteria and that may help my symptoms and build up a more well-rounded gut microbiome. Because of long-term antibiotic treatments that were prescribed because of my Crohns, my gut microbiome is lacking diversity and particular kinds of microbes. There is a project in Gut Love called Landscape of Lost Microbes. This work consists of a series of petri dishes, with my gut bacteria next to Dr. Will DePaolo’s bacteria. Will generously invited me to join his lab in 2016 and we have an ongoing collaboration. Will is the Director of CMiST, The Center for Microbiome Sciences and Therapeutics at the School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle. Our first experiments were to plate our stool samples next to each other to compare, Will as the “healthy” subject, and me as the “sick” one. One of our first discoveries was that my side of the petri dish repeatedly came up blank, missing microbes—whereas Will’s side was flourishing.

To really test the bacterial dermal transfer idea, I need to conduct lab research to test this further. Ideally, I will isolate various bacteria from other people’s gut microbiome that I will subculture and then regrow for my use for this dermal transfer.

Rail: Just after visiting Gut Love, I went to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts to see Thomas Eakins’s famous painting from 1875, The Gross Clinic. I was immediately brought back to the scene in Fecal Matters in which a doctor performs a Fecal Matter Transplant for a woman suffering from C. diff. The positioning of the patient is not only the same, but both doctors are demonstrating their fascinating procedures to a curious, though partly “Grossed” out audience. As the 21st century microbiome continues to be analyzed, classified, and even commodified, what are your hopes and concerns about procedures such as FMT?

High: Along with the scientists and researchers we interviewed in Fecal Matters, I am a bit suspicious of FMTs—but also really excited about the possible futures. Collaborator Guy Schaffer and I also worry about feces becoming a commodity and its entrance into the capitalist arena as a product to be bought and sold. This is why we also created the video about a new app, OkPoopid, where participants can line up speed dates with potential fecal donors for DIY at-home FMTs. Making feces as a therapy available to a general public and part of the gift economy.

Rail: In your past and current work, you seem quite interested in the “weird,” a term that colors the space between our learned individualism and the reality of our interconnectedness—our true intimacy with the strange, the abject, the other. The closer we look at ourselves, the weirder and more amorphous we become, like Haraway’s symbiotic lichens. In America we are raised against weirdness—chock full of antibiotics and hyper-sanitized against every germ, good and bad. We are taught to pride our individualism, not our liminality. In this precarious age, I wonder if you believe the weird can save us from self-destruction?

High: These alternative interests of mine have been a problem since I was very little. My mother always teased me saying that my first word was “no” and my interest in things fell outside the “norm.” My parents were wonderful people, but very conservative, and they had hoped I would be like them. Ah well…

Perhaps the weird will save us from self-destruction. But we are probably doomed for self-destruction no matter what. That which is weird can provide us with alternative approaches, ways of seeing new combinations, novel relationships, and alliances. This is what will save us if anything can—maybe not from self-destruction—but from doing harm to each other, giving us new strengths and options.

There are so many amazing philosophers, theorists, artists, and environmental humanities scholars who are considering how to break out of our old Cartesian tenants, critiquing biopolitical and bioeconomic realities, questioning the ethics of de-extinction and beyond. Our understanding of the agency of non-human creatures, be they animals, plants, bacteria, fungi, whole organisms, or cells, needs to be stretched and nurtured. Rats laugh, bacteria can be happy. We need to consider our connections in so many ways.

Notes

Haraway does not use the word “posthumanist.” In her most recent book, she describes herself as a compostist not a posthumanist: “We are humus, not Homo, not anthropos; we are compost, not posthuman.” And, “Critters are at stake in each other in every mixing and turning of the terran compost pile. We are compost, not posthuman; we inhabit the humusities, not the humanities. Philosophically and materially, I am a compostist, not a posthumanist.” See Donna J. Haraway, Staying With the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University, 2016), 55; 97.

History of Shit, (1978) by Dominique Laporte (Cambridge: MIT Press, reprint, 2002).

Oliver Kellhammer and Kathy High co-created the glass colons together working with glass-blower Bill Jones.

Straight Talk with Kathy High / SciArt Magazine

“Straight Talk with Kathy High,” Featured interview with editor Julia Butaine, SciArt Magazine, April 2017.

Julia Swanson, SciArt Magazine: As a cross-disciplinary artist, you often explore science, technology, and biology. How did you start creating this type of research-based art?

Kathy High: I first came to this science, technology, and biology research-based art through my early videos. I lived in New York City from the early 1980s on and at the time I decided to just focus on video production as my means of expression. In the late 1980s and through the 1990s, I was creating works which were rooted in documentary that melded fact and fiction. I started a series entitled "Women in Medicine" that looked at various aspects of women as patients in relation to our medical establishment. I had been a patient and was incredibly frustrated by the ways I was often treated. I started researching the history of the medical establishment in this country, the American Medical Association (AMA). I made a video in 1989 entitled I Need Your Full Cooperation where I juxtaposed feminist examinations of medical practices, narratives of patient treatments, and archival footage. In the video I dramatized Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “rest cure” in an adaptation of her 1892 story The Yellow Wallpaper, and included critical commentary by activist/writer Barbara Ehrenreich and historian Carroll Smith-Rosenberg. I suppose this was my first venture into research-based work. I had read quite a bit about the development of the AMA, and the early eradication of midwives from practice through the “professionalization” of the medical field – doctor’s maintaining particular control around women’s reproductive health. It is surprising how threatened women’s reproductive rights still are today.

"Underexposed: Temple of the Fetus" (1993-4). Video. 60 min. Video still courtesy of the artist.

In 1990 I co-produced a video with Paper Tiger TV called Just Say Yes: Kathy High Looks at Marketing Legal Drugs. This tape was a critique of pharmaceutical company practices and the coercion of doctors to use their goods. Who suffers in this process? We researched the methods used by the pharmaceutical industry to both advertise and push big pharma drugs. Great archival footage accompanied my breakdown of the chemical pathology in western medicine as a means of social control and as market commodity. The episode began with an illumination of the ways that doctors are coerced into prescribing certain drugs by the pharmaceutical companies, as well as how the refinement and dispensing of controlled drugs has been instrumental in creating the social prestige of medical doctors.

Then in 1993 I produced Underexposed: Temple of the Fetus, an experimental documentary about new reproductive technologies – mixing science fiction with expert interviews, archival film footage, and text. I was reading works by radical feminists such as Sandra Harding (author of Whose Science? Whose Knowledge: Thinking from Women's Lives) and Gena Corea (author of The Mother Machine) who were inquiring into the ethics of new reproductive technologies. Who had access to them? Who benefits? Who is harmed? What are the consequences for female bodies? It was a particularly crazy moment because in-vitro fertilization had become successful and there was a big move to promote assisted reproductive technologies. It was really amazing to engage with these feminists who critiqued the technologies, technologies which perhaps viewed women only as “vessels.” I interviewed sociologists, journalists, activists, nurses, fertility doctors, bovine veterinarians, surrogate mothers, and more, trying to get some understanding of the field.

"Lily Does Derrida: a dog’s video essay" (2010-12). Video. 29:30 min. Video still courtesy of the artist.

This experimental work used both narrative and documentary to “unhinge” the viewer, making one destabilized and unsure as to what was fact and what was fiction. Underexposed: The Temple Of The Fetus examined ways the news media shaped our perceptions and social attitudes around new reproduction technologies and genetic engineering. The fictional portion of the video followed the political awakening of a TV journalist who unearthed the possible complications of these new technologies while investigating them for her medical news series.[1] As part of the dramatized portion of Underexposed, in a fake interview with the Director of New Reproductive Technologies, the doctor proclaimed: “This is not just a baby. It is a national initiative.” These science fiction depictions of IVF, donor insemination, and designer babies pointed to the advancing reproductive technologies, hinting towards the types of selective breeding and eugenics that are making a resurgence today.

In 1994 I made a project for Deep Dish TV entitled High-Tech Baby-Making: North and South.[2] High-Tech Baby-Making: North and South was an edited collection of documentary shorts by feminists from Germany, France, Brazil, Mexico, India, and the United States, reflecting upon the use of reproductive technologies around the world. This collection of excerpts looked at the state of reproductive conceptive and contraceptive technologies for women. The status of first- and third-world reproductive politics were reflected in these excerpts, such as the contrast of overpopulation issues in so-called developed countries, and infertility problems in so-called developing ones.

This was the final work in the Women in Medicine series.

[1] Script by Karen Malpede, performers included Peg Healey, George Bartenieff, Annie Sprinkle, Shelly Mars and Jules Backus.

[2] This was co-production with Harriet Hirshorn for the Deep Dish TV collective as part of the series “Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired “ about women and health. It was broadcast on cable television nationally and internationally. Deep Dish TV is a NYC collective who send packaged programs out through satellite – thus works were transmitted from satellite to satellite across the country, and then downloaded by local public cable stations everywhere – a kind of genius distribution system – see http://www.deepdishtv.org/

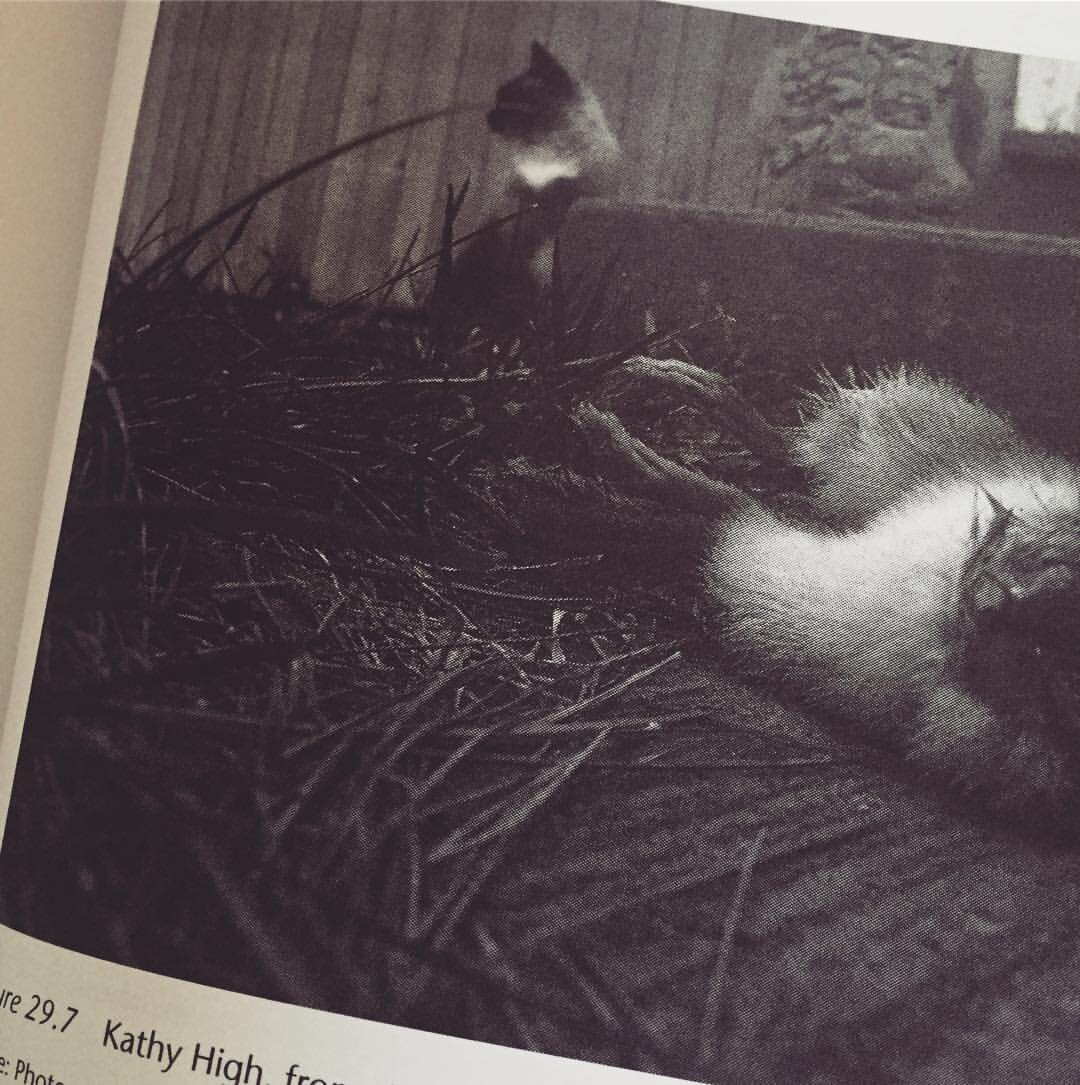

"Embracing Animal" (2005-06). Transgenic rats, metal, wood, glass, electronics. 20’ x 20’. MASS MoCA. Photo credit: Adrian Garcia.

JS: In several of your videos you explore the dynamics of interspecies relationships and communication, specifically the relationship between animals and humans. Can you explain what is it that you fine most intriguing about the human and animal relationship, and why?

KH: I find this area to be one of the most challenging and at the same time it is incredibly important. I have always been respectful of our non-human colleagues since I was a child. I argued with my middle school biology teacher about the intelligence of dolphins and the fact that we do not understand how to properly gauge animal intelligence or sentience – as my teacher argued for the superiority of humans over all earthly creatures. We are trapped in the Western Cartesian dilemma of placing humans above all other non-humans. This is how we are taught and it is a teaching that’s hard to undo. We still live this reality.

"Animal Attraction" (2000). Video. 60 min. Video still courtesy of the artist.

Now I teach methodologies of “undoing” these older ways – or rather, as Donna Haraway would say “staying with the mess.” And in the end, respect is the best tool I have that ultimately works. Curiosity, learning, listening, watching, loving – all with respect.

I first started working with animal communication in the late 1990s. It was not as popular a topic as it is today. Now animal studies is in vogue and there are tons of amazing contemporary writers and artists addressing the field[3] who are thinking through these questions of how we can ultimately understand and relate with each other. I have engaged with this tangle of thinking through many of my works, including the video Animal Attraction about animal communicator Dawn Hayman, Lily Does Derrida: a dog’s video essay, where my deceased dog Lily grapples with the theories and thinking about human-animal relations by the late Jacques Derrida, Embracing Animal, which housed three live transgenic rats related to my own diseased body, among other works.

[3] Persons such as Donna Haraway, Cary Wolfe, Vinciante Despret, Susan Squier, Giorgio Agamben, Eben Kirksey, Vicky Kirkby, Thom van Dooren, Deborah Bird Rose, Ron Broglio, Stacy Alaimo, Una Chaudhuri, Erica Fudge, Carol Adams, Giovanni Aloi, Nigel Rothfels, Jonathan Burt, Akira Mizuta Lippitt, Monika Bakke, Animal Studies Group, Human Animal Research Network Editorial Collective and artists such as Margaret Atwood, Terike Haapoja, Eduardo Kac, Beatriz da Costa, Kira O’Reilly, Catherine Chalmers, Steve Baker, Olly and Suzi, Bryndís Snæbjörnsdóttir and Mark Wilson, Art Orienté Objet, Carolee Schneeman, Sue Coe, Perdita Philips, Mark Dion, Sam Easterson, Lee Deigaard, Natalie Jeremijenko, and many more…

"Bank of Abject Objects" (2015). 24” x 8”. Glass, honey, ceramics. Image courtesy of the artist.

JS: I'd like to talk about poop for a minute. As a culture it is something we try not to talk about, but in your project Bank of Abject Objects you bring it front and center and create a DIY stool bank for preserving "healthy" stool. You also posit that in the future stool could become a valuable commodity owing to its multiple therapeutic properties. What first interested you in this as a theme?

KH: Who isn’t interested in poop, if they are really honest with themselves!? I became focused on poop early on in my life as I have Crohn’s disease, an inflammatory bowel disease. Poop is one of our body’s byproducts, an outsourced continuum of ourselves that is updated daily. It is a registry of our intake, our current health, our food and water absorption, and our fascination with filth, order, dirt, and waste.

Currently there is a growing awareness in waste studies about the value of our poop. What can we do with poop? How can we use it as a commodity? With the increasing appreciation for the importance of our poop, we have also come to see how it can be used differently than we previously thought. So, for example, with the rise in antibiotic resistance, we may want to store a sample of our poop prior to a treatment of antibiotics – just in case we would like to revisit that older gut biome configuration if the antibiotics backfire. We might consider storing a stool sample prior to international travel, or while one is younger and healthier for old age. No one really knows the complete properties of poop as of yet, but I am banking on “healthy” poop (whatever that actually means) becoming an important traded good in our bio-futures.

"Kathy As Bowie" series (2015). 42” x 30”. Photograph. Photo credit Eleanor Goldsmith.

JS: In "Kathy As Bowie" you reflect on the importance of David Bowie in your life by paying tribute to him through a series of photographs that mimic some of his iconic portraits, and you reflect on the possibility of adding his gut microbiome to your own. In many ways this is a very intimate and personal project. What was the process that went into developing this piece?

KH: I have been researching the human gut microbiome for a number of years now. This field is very much monopolizing the public’s imagination at present as we discover how much the microbiota in our guts influence our everyday decisions – such as what we eat, how we think, our moods, etc.

Because of this human gut microbiome research, I have produced and directed a video documentary about fecal microbial transplantation or FMTs, entitled Fecal Matters (to be released late this year). The creation of this video has allowed me to interview scientists, gastroenterologists, and researchers in the field related to FMTs.

Fecal microbial transplantation is the transfer of one person’s poop into another person’s body. This can be done in a variety of ways, but the goal is to transfer “healthy” poop to help stabilize the recipient’s own microbiome.

"Kathy As Bowie" series (2015). 42” x 30”. Photograph. Photo credit Eleanor Goldsmith.

A few years ago, a good friend of mine (Kira O’Reilly) asked me whose poop I would want if I could have a FMT from anyone in the world. In response, I blurted out “David Bowie.” I look at a FMT exchange as still a bit mysterious and unknown. What exactly is in our gut microbiome? What “signatures” do our gut microbiomes carry about our bodies, our characters? Are our gut microbiomes really transient and changing all the time, or do they also store a kind of “history,” a memory and a longer life signature?

Thinking about David Bowie, I realized that he had been such a hero to me when I was younger, as he was such a trickster character, a risk-taker, and someone who could transform himself constantly. I found Bowie to be inspiring and he offered courage. I wanted his poop to perhaps also transfer to me (literally) some of that magic he offered us all.

From the RPI student group Biodesign project.

JS: As a professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute you had the opportunity last year to work with students in New York's annual BioDesign Challenge. What excited you the most about the work the students produced?

KH: My RPI students created a speculative project entitled Live(r) Clear – a living biofilm enzyme membrane that would line your toilet to help collect discarded pharmaceuticals such as estrogen from entering our waste water systems.[4]

This truly collaborative team of engineering, arts, and architecture students consulted RPI scientists, visited our local wastewater treatment plant, envisioned with 3D print models, and conducted extensive research to develop their project for the BDC given theme of “medicine.” I was incredibly impressed with this truly interdisciplinary team and their ability to collaborate and create a biodesign project for the first time.

I am committed to this idea of hands-on learning through participatory critical methods that place creative practices alongside engineering and science. The artists and engineers, computer scientists, biologists, science technology studies, and marketing students (among others) all contribute from their various disciplines and knowledge sets. I find that through this process everyone develops a newfound respect for each others’ skill sets.

While the BDC didn’t win an award, we all found the process incredibly stimulating. And the students are investigating obtaining a patent for Live(r) Clear!

[4] The student team consisted of inventors Amanda Harrold (environmental engineer), Kathleen McDermott (artist), Jacob Steiner (biomedical engineer), and Perrine Papillaud (mechanical engineer) with help also from Jerry Huang (architect).

"Family Bio-crest" (2016). Agar plate and fecal bacteria. De Paolo Lab USC.

JS: What are you working on right now?

KH: I am currently creating works for an exhibition that will occur this fall, 2017, at the Esther Klein Gallery, as part of the Science Center in Philadelphia, curated by Angela McQuillan. Some of the projects for the exhibition stem from work I started last year. I have been working in collaboration with a human gut microbiome scientist/immunologist, William de Paolo, PhD, who is Associate Professor of Medicine at the University of Washington Medical Center and Director of the Center for Microbiome Sciences & Therapeutics (CMiST) in Seattle. Will is helping me to develop various projects for this exhibition that also relate closely to his work.

One such project is Family Bio-Crest, a project researching gut microbiota and the bacteria and micro-organisms that inhabit our gut. I want to discover if family members share similar (or dissimilar) gut microbes because they share (or shared) a living environment, thus possibly giving families a particular gut bacterial/fungal community signature and profile. This project aims determine how much gut microbiota families share. Another project Bacterial Blanket, will speak to my “missing” gut bacteria (as a Crohn’s patient) and provide bacterial replacement therapy – with a nod to the “security” blanket that many of us had as children, treating the blanket as familiar object filling in for the missing parental unit(s).

Interview with Jessica Ullrich / Antennae: The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Interview with Jessica Ullrich, in Antennae. The Journal for Nature in the Visual Arts. The Interview Issue #1, Issue 38, Winter 2016, online journal, UK.

>>DOWNLOAD PDF

Piper in the Woods: Men Becoming Trees / Routledge Companion to Biology in Art & Architecture

Piper in the Woods: Men Becoming Trees, chapter in The Routledge Companion to Biology in Art & Architecture, Eds. Meredith Tromble and Charissa Terranova, Routledge.

>> DOWNLOAD PDF

Piper in the Woods: Men Becoming Trees

The Routledge Companion to Biology in Art & Architecture, Eds. Meredith Tromble and Charissa Terranova, Routledge.

Gut Love / Food Phreaking Issue 03

Gut Love, essay in Food Phreaking Issue 03, Eds. Wendy Russell, Sylvia Duncan, Zack Denfeld, Emma Conley and Catherine Kramer, published by The Center for Genomic Gastronomy, Sept., 2016