The History of Shit — The Forgotten Scatomancer: Challis Underdue’s Excremental Vitality and the Medical Cultures of Modern Great Britain, (2017) by Guy Schaffer

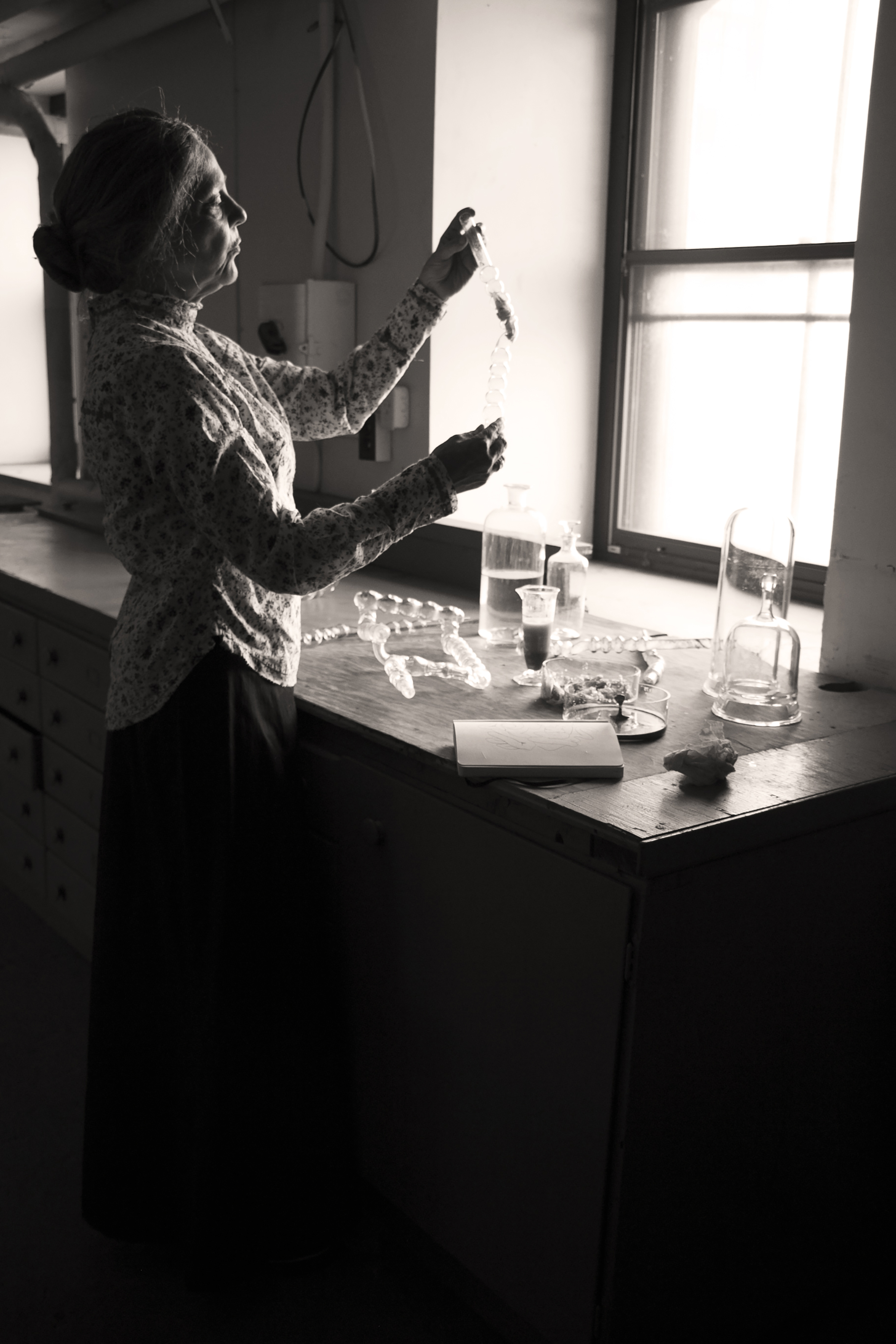

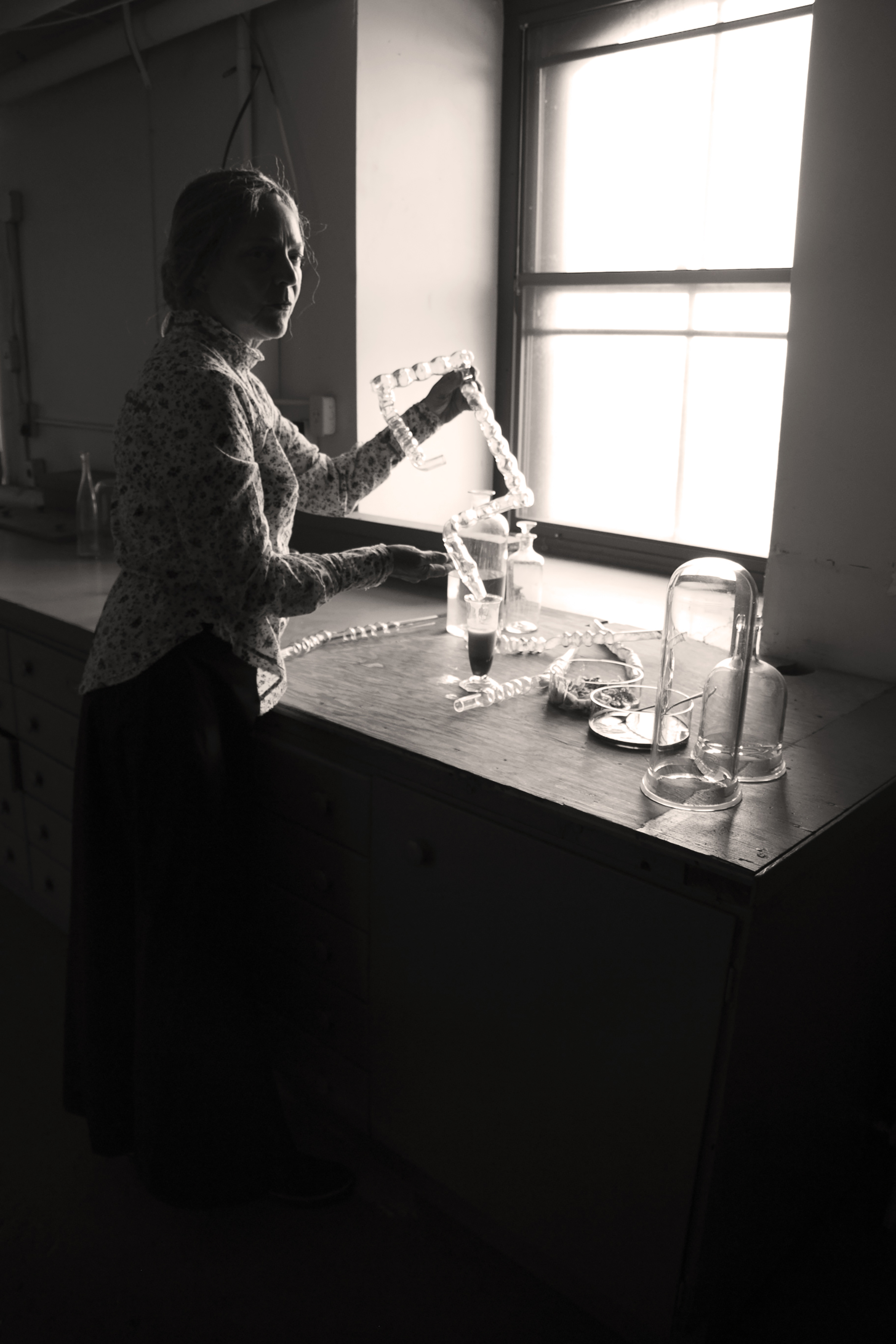

Challis Underdue: The Forgotten Scatomancer (2017). Photo: Shannon K. Johnson.

Conceived by:

Kathy High and Guy Schaffer

Written by:

Guy Schaffer

Photography:

Shannon K. Johnson

Production Support:

The Mütter Museum, the F.C. Wood Institute, and to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

The History of Shit / Challis Underdue: The Forgotten Scatomancer: Challis Underdue's Excremental Vitality and the Medical Cultures of Modern Great Britain (2017) by Guy Schaffer

1: The Scatomancer

If you mention the name Challis Underdue to the average student of proctology, you might elicit a variety of colorful epithets:

Scatomancer,

The Last Rectal Magician,

High Priestess of Feces.

Until recently, Underdue has been largely written out of the history of feces, or treated only as a sort of cautionary tale about the damaging roles of superstition and stubbornness in the early-modern rectal explorations that have come to define the field as we know it today.

Whether Underdue has been excised from the history books because of her sex, unfounded rumors about her being “unnatural” or “inverted,” or simply for the audacity of her theories is hard to say. It’s well known that proctology was a conservative field in the 19th century: women were not allowed into meetings of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society (except as anatomical models), and the rectum was considered too unclean and unfeminine a topic of study for midwives. (That the birth process frequently produces an enormous amount of feces was apparently ignored by these men of science).

Thanks to the recent unearthing of her notebooks at her house in Letchworth (now, ironically, an expensive day spa that offers, among other things, fecal transplants), historians have been able to learn much more about Underdue, and to challenge the one-sided representations of her we so often see. Among historians of proctology, Challis Underdue is now understood as a maverick, not a quack: the inventor of the anuscope, a prescient believer in the gut microbiome, and a champion of intestinal health.

!!!

2: Night soil

Born in 1790 in Hertfordshire, England, Challis was the youngest of five children. Her father, Charles Underdue was a “nightman”—a waste carter who collected refuse in the city and delivered it to farmers in the countryside. Her mother, Anne Underdue (nee Brown) was tried for witchcraft in 1799, and spent much of Underdue’s childhood in prison. This left Challis in the frequent care of her father, who would take the precocious young child on his rounds, exposing her at an early age to the filth of London.

The modernization of London began with its excrement. Cesspools and middens of the Middle Ages—public latrines that were only emptied twice a year or less—gave way to the more civilized “pail closet,” private waste systems that would be emptied out weekly or even nightly. The Underdues were a pioneering family of “nightmen,” entrepreneurs who, for a fee, would collect “night soil”—human leavings—and deliver it to rural farmers in the surrounding counties. While hardly “gentlemen,” the Underdues had created a profitable business for themselves.

Many early commentators presumed that Challis’ involvement in the trade was a form of abuse on Charles’ part—even today, many people would assume that a young woman of middle class standing would be thoroughly disgusted at the prospect of a nightman’s work. However, Challis Underdue, perhaps owing to some genetic (or microbial!) inheritance from her father, relished the opportunity to gaze into the chamber pots of London. Her diary demonstrates some of her amazement:

Father and brothers turn up their nose at the smell of the city, but I find so much excitement in it: what the leaver might tell you about his life through his leavings!

While it was highly unorthodox for a nightman to think much about the contents of a chamberpot, Challis’ diary suggests that she was able to charm her father into a form of fecospection:

At one stop always, I set aside the customer’s faeces for the purposes of a game that I developed on my own. Noting the address (but holding it secret), I share the day’s “mystery pot” with father on the road back to the country for him to smell and examine, and ask them to guess which customer it came from! Father is desperately bad at the game; he often guesses a generator who is a totally different sex, age, and neighborhood from the actual owner of the chamber pot. Of course, I only play as the chooser of the pot because when I am the guesser, it is far too easy and I am constantly right; the smells and colors of different faeces are all so distinct that each is like a single rose of a single variety, growing in the botanical garden.

The work that made Underdue famous (or should have, were it not for other contingencies of history) emerged largely from the night-pails of her youth: a fascination with feces that would guide her toward a theory of the bowel that no other scientist of her time would ever approach. Learning to live with large quantities of human stool, in close, exuberant intimacy, allowed Underdue to see further than any of her contemporaries–indeed, further than many of the thinkers who came after her. It remains to be seen how many of Underdue’s insights will be seen to be accurate as gastroenterology and proctology enter the third millennium—though recent explorations of the gut microbiome and fecal transplants promise a possible future for Underdue—not as the high priestess of feces, but as a truly gifted scientist whose dream of intestinal life set the agenda for research hundreds of years after her time.

…

3: Fermentation experiments and the

excremental vitality theory

Historians have debated the scientific origins of Underdue’s

excremental vitality theory, which many see as a precursor to what we now understand as the gut microbiome. For many years, the dominant theory held that Underdue was cleverly appropriating animacular theory (a discredited 17th-century concept of disease caused by of microscopic animals) for use as a correction to humoral theory, which framed all illness as an imbalance between the body’s humours. This theory is somewhat consistent with her writings, in which balance between the inhabitants of the intestine is the cause of either health or illness. Feminist historians of science have suggested that her interest in a living, animate intestine was inherited from her placement within the cultures of midwifery, which challenged the mechanical metaphors of medieval and modern medicine through its depiction of an irreducibly complex body that is to be lived with, rather than controlled.

The unearthing of Underdue’s diaries has encouraged a new explanation for the origins of excremental vitality, as a sort of microcosm of the complexities of human society, refracted through the “lens” of the anus. The following passage, in an entry from 1807, might describe the exact moment of origin of the concept:

Ass above, so below, it is written by Hermes Trismegistus. This wisdom of the ancients has always seemed clear to me: as I peer into the brown mirror of the chamber-pot, I wonder whose reflections I look into. The city of smoke, with all its factories and markets and fancy ladies is reproduced in mirror image in the city of shit that my father and I inhabit. And this city of shit must, I suppose, be mirrored in microcosm on the opposite side of the anal lens—each Londonite’s bowel functioning as the streets of his own body politic. How I would care to learn how these intestinal villages operate: what law can govern shit?

It is unclear if her misreading of Hermes Trismegistus is honest or merely a private joke.

Wherever the concept of excremental vitality emerged, it was a central theoretical entity in her fermentation experiments from 1843 to 1849. In these experiments, she aimed to create a balanced fecal system from first principles.

Her ideas built on the work of David MacBride, who had likewise sought to mimic the colon in order to understand the dynamics of feces. In a series of experiments in Experimental essays on medical and philosophical subjects (1767), MacBride sought to model the process of digestion by watching macerated food that was kept at body temperature for an extended period of time. MacBride was attempting to demonstrate that the process of digestion was not merely putrefaction as was commonly thought, but fermentation.

Where Underdue dissented was in her respect for the complexity and uniqueness of feces:

MacBride, in his effort to create an artificial digestion, is blind to the specialness of any person’s feces. I imagine that, despite his pretension to scatology, he would have been hard pressed to distinguish his feces from that of his wife or even that of a hound. Surely an experiment on the fermentative process in the large intestyne must be attempted that recognizes that any instestyne is unique. How best to capture this uniqueness, then?

Seeking an account of a truth that she had held onto since childhood—that feces could identify its maker, like fingerprints or the bumps on a skull, Underdue embarked on six years of rigorous experimentation, trying to mimic the fermentative process of the intestine.

This involved several innovations in fecal culturing, some of which have been reproduced in a contemporary context, others that have yet to see wide methodological acceptance. The glass colons that she used were designed to mimic the shape of the intestinal environment, while still allowing her to see the movement of a bolus through the canal. In order to maintain an even temperature, she would spend whole days with the colons pressed against her skin under her dress. Remarkably, without any understanding of “aerobic” or “anaerobic” fermentation, she had the insight to burn a piece of charcoal in the glass tube in order to minimize the oxygen.

The breakthrough of Underdue’s work, though, was when she first recognized that true feces could not be created without the addition of feces.

After too long producing sludge that was alternately putrid or sweet, but never fecal, it occurred to me that it might prove impossible to reproduce the splendor of excrement from pure ingredients. While the alchemists might describe excrement as a “base material”—substance with all value removed—I am led to wonder if excrement might have some spark, or liveliness, that is altogether irreplaceable when attempting to start from raw ingredients.

This is now the third week with the “transplant,” and it pleases me endlessly to recognize that the substance produced by the apparatus continues to be distinctly fecal, and distinctly mine. The colon has been regularly producing masses of what appears to be excrement—once or twice a day. Given that my original contribution to the system weighed just over an ounce, the two pounds of—my own feces—that it produces daily seems to be the product of the system itself. I know better than to stretch my ideas beyond the evidence at hand, but this suggests two related concepts that bear further scrutiny:

– The vitality of excrement is necessary for the production of true excrement.

– The uniqueness of one person’s feces is tied not to their body or their soul, but to the vitality of their excrement.

What Jacques de Vaucanson had claimed to do 110 years earlier with his Canard Digerateur–mimic digestion mechanically with his digesting duck automaton in 1739–Challis Underdue had finally accomplished in reality. What finally emerged from these colons was a fully-fleshed out account of feces as a living thing–not an end result, or degenerate substance, but as something capable of producing life.

Challis continued to maintain the glass colons until the end of her life in 1854, keeping detailed notes on her studies, but never publishing her findings. While a study of her journal from 1849-1854 would be edifying for any student of the microbiome, a series of experiments in 1851 might prove particularly enlightening: using feces that she had sampled from willing patients, she was able to demonstrate the excremental transformativeness that can unfold when two vitalities inhabit the same colon. This led her to a develop a question that would not find an answer within her lifetime: if one’s excrement can be transformed, can the person be transformed as well?

===

4: Challis the midwife

Underdue was unmarried, and inherited no significant fortune after her father’s passing; she was also never educated in any formal capacity, nor was she in a medical community strictly speaking. Therefore it is necessary to give an accounting here of how Underdue, living at a time when professional options were highly limited for women, was able to make some of the most surprising—if undervalued—medical breakthroughs of her time. Simply, it was a combination of three factors: her entry into the field of midwifery, her efforts to save that field in the face of masculine takeover, and her intimate friendship with the surgeon James Miranda Barry.

Underdue’s entree into midwifery was traditional enough: when she was a teenager, her aunt, Etta, explained “the flowers” to her—the 18th century term for menstruation—and this basic health education brought Challis into Etta’s informal network of traditional healers. Etta was likely the first to see in her niece the genius that we now recognize her for, and apparently exerted some pressure on Challis to learn more about midwifery.

Giving in finally to my aunt’s entreaties, I begrudgingly accompanied her to a birthing—and oh, how I regretted my initial disinterest! What strength we, the “weaker sex” are capable of! The woman came fully apart in the process: this composed human lay on the bed, then, denuded, she split in two, lost her voice screaming, and squirted forth blood, feces and baby from her lower quarters. The process was an inspiration to me; I pity the male sex to lack this transformative experience in their lives.

As with all experiences in Challis’ life, she remembered best the scatological details. This is a blessing for scientists, though: her focus on the scatological aspects of childbirth enabled much of her later explorations of feces as a living thing.

By the time Challis was 25, she had earned a reputation as a widely-

respected midwife. While her midwifery was expert on its own, she also brought to this field a concern with the scatological. From the very beginning of her career, she fought against the then-prevailing assumption that a mother should try not to defecate while giving birth. She even developed a breathing technique modeled after a bowel movement. Underdue was even more daring with this approach following her excremental vitality experiments of 1843-1849, and would advocate for babies to come into greater contact with their mothers’ feces on the birthing table, in order to spark the vitality of their bowels.

The field of midwifery was in a state of transition in the late 1700s and early 1800s: knowledge and practice that had once been passed down through informal networks of women was being challenged by the male-dominated professional field of obstetrics. Detailed accounts of the transition might be found elsewhere; in order to understand the position Challis occupied when she entered the field in 1807, it’s important to recognize that there was a battle of the sexes to establish authority over fertility, pregnancy, and birth. While the takeover of the field by masculine obstetrics might have felt inevitable to other midwives, Challis was never the type to give up in the face of even unbeatable odds.

Instead of fearing the scientific thought of the new doctors of birth, Underdue decided to try to learn to do this type of work herself. She took every opportunity she could to interact with medical knowledge, even traveling to Edinburgh to work first as a nurse at the Royal Infirmary, then as an anatomical model at the University of Edinburgh Medical School. While her diaries show a great deal of detailed notes from her time here, the greatest discovery she made in Edinburgh was the medical student James Miranda Barry.

While many of the students and teachers seem to forget that I am a living model, and not a corpse, there is one who treats me with kindness, almost empathy. He is diminutive, with delicate—handsome, even—features and a high voice, I suppose he must be much younger than the other men.

Underdue becomes quite close with Barry, and he begins to, in small ways, provide her with access to the medical knowledge offered by a university education. Historians are divided on whether the two of them became romantic. There is no evidence, either in their letters to one another or in either of their private journals, that their feelings toward each other were physical. We do know that Underdue became one of the few people entrusted with Barry’s dangerous secret—that he had grown up until then as a woman, and had taken on the name “James” and a masculine identity in order to attend medical school. Whatever the nature of their relationship, Underdue and Barry kept on a lifelong correspondence, which is how Underdue became familiar with many of the medical and biological theories of her time. Long past Underdue’s death, Barry was one of the few people who seemed to respect Underdue as a scientist and creator of knowledge.

%%%

5: Underdue’s Inner Voyage

The term “underdue” is still used in some medical schools as a name for an endoscope, but few recognize the origins of the term. The common assumption, that it is some crass joke about the backside, is sometimes challenged by an even less-accurate correction: that Challis Underdue was the inventor of the device. Neither is fully true: Underdue developed the anuscope, and even wrote up specifications for a sigmoidoscope, but never envisioned a device that made it past the sigmoid.

The colloquialism instead springs from the imagination of Georg Wolf, the manufacturer of the first semi-flexible gastroscope in 1932, who was inspired, in part, by Underdue’s writings:

Think of it—would it not be enlightening to truly enter the colon of your fellow man? This, truly, is the next frontier of science: to take something like the Holy Voyage of “Saint” Challis, who so fixated on shit that she could imagine herself flying into the gut to live among its “animalcules.”

Within the proctological community, Wolf’s evocative descriptions of endoscopy were so well known that his first prototype was referred to as an “Underdue” because it seemingly reproduced the experience that Challis describes in The Inner Voyage,—her only published manuscript until the discovery of Underdue’s notebooks in 2007. That The Inner Voyage could be published, and not any of her experimental works, is a testimony to the rigid expectations of women in England in the mid-19th century: a woman could be the author of a speculative fiction book, or an account of a holy vision (scholars still debate which of these Underdue was trying to accomplish in her Voyage), but not trusted to be the producers of reliable scientific knowledge.

Underdue’s book tells the story of a person with a life much like herself—a doctor with a deep curiosity about the intestine, but who has little access to a scientific community—who dreams one night that they travel into their own colon, meeting all sorts of fanciful life forms there.

Once through those velvet curtains of the anus, I was welcomed into a warm and inviting vestibule, which I recognized from my own explorations as the rectum. It was lit from inside by a shimmering luminiferous quality, and I struggled to make sense of it, but also knew that at the end of this hall was a secret area that called to me, a bend that had previously been unconquerable to even the longest proctoscopes in my kit. I moved, floating—seemingly weightless—toward this turn into the unknown, uncertain whether pulled along by the force of my curiosity, or by something outside me that knew this to be where I belonged.

...Having encountered animalcules on the microscope slide, and the leftovers of various vegetative and animal tissues, some of the beings I met here were familiar. But within moments I had been able to touch and see such variety of animalcules that I was speechless.The sheer number of different life-forms dancing before me testified to a complexity of the society of the colon that I had never considered: they were more lively and more varied than the vendors and shoppers at Borough Market, or even those on the streets of Paris that I have read about in books. It would surprise me if the variety of all the people of the world could parallel the variety I saw here spread out in the intestines before me: there were variations in size, in activity, in shape, in motion: some were violent, trying to eat the others, while others seemed to work together harmoniously...

...the change arrived simultaneously as an internal feeling, and as a visible alteration in the motion of the beings around me: something had shifted, and a threat was upon us. The changes in the activity around me were miniscule at first, but cascaded into a perfectly other kind of chaos than what I had seen when I first entered this world. These beings had once interacted in a way that felt mutualistic—even in consuming one another, they seemed to act with a kind of respect that was foreign to the human world. However, in this transition, these interactions became violent: being would kill being without eating it, they would rail at the boundaries of this space, crying out in pain. All the harmony that had suffused the space was replaced with fear and trembling and pain. The balance was lost.

The novella follows its protagonist through the colon, all the way to the cecum, where they eventually meet the specific kind of animalcule responsible for the change they witness in the social fabric of the colon. It has been a matter of some speculation among the Underdue realists—those who believe the story to reflect an actual astral journey that Underdue undertook—to identify the antagonist of The Inner Voyage; many scholars have pointed to Giardia, which was known at the time. Clostridium difficile has been a more recent suggestion, though this would, of course, assume that Underdue’s vision gave her access to knowledge that would only have been available through enormous foresight.

The influence of The Inner Voyage is impossible to overstate. Georg Wolf is explicit that it was his childhood fascination with Underdue’s Voyage that inspired his attempts to see into the colon. Perhaps the most famous example is Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which likewise features a curious female protagonist (the sex of Challis’ doctor is never stated, but most literary scholars agree that the doctor is intended to represent Challis herself) who learns about herself by undertaking a mysterious journey into a dark tunnel.

It has remained unclear since the novella’s publication in 1851 whether Underdue meant for it to be read as purely fictional, or an account of a vision she had experienced, or even of an “astral” voyage that had led her to truly mystical knowledge—though she makes no effort to explain the forces that pull her into the colon. Based on the obvious echoes of her glass colon experiments in Voyage, it is possible that this sort of account was the only conceivable way that Challis, a woman without any formal education, could share her theories with the broader scientific community.

While much ink has been spilled debating the events described in The Inner Voyage and their reality–in fields as far apart as gastroenterology, feminist science history, and occultism, it is possible that the reality or unreality of the account has very little to do either with the life of Challis Underdue, or with the current conduct of gastroenterology. Instead, we should perhaps see it as simply a tool for the communication of ideas between a forgotten thinker of the 19th century and the contemporary pioneers of our fecal future.

—The Forgotten Scatomancer: Challis Underdue's Excremental Vitality and the Medical Cultures of Modern Great Britain, by Guy Schaffer as part of the exhibition The History of Shit (2017).